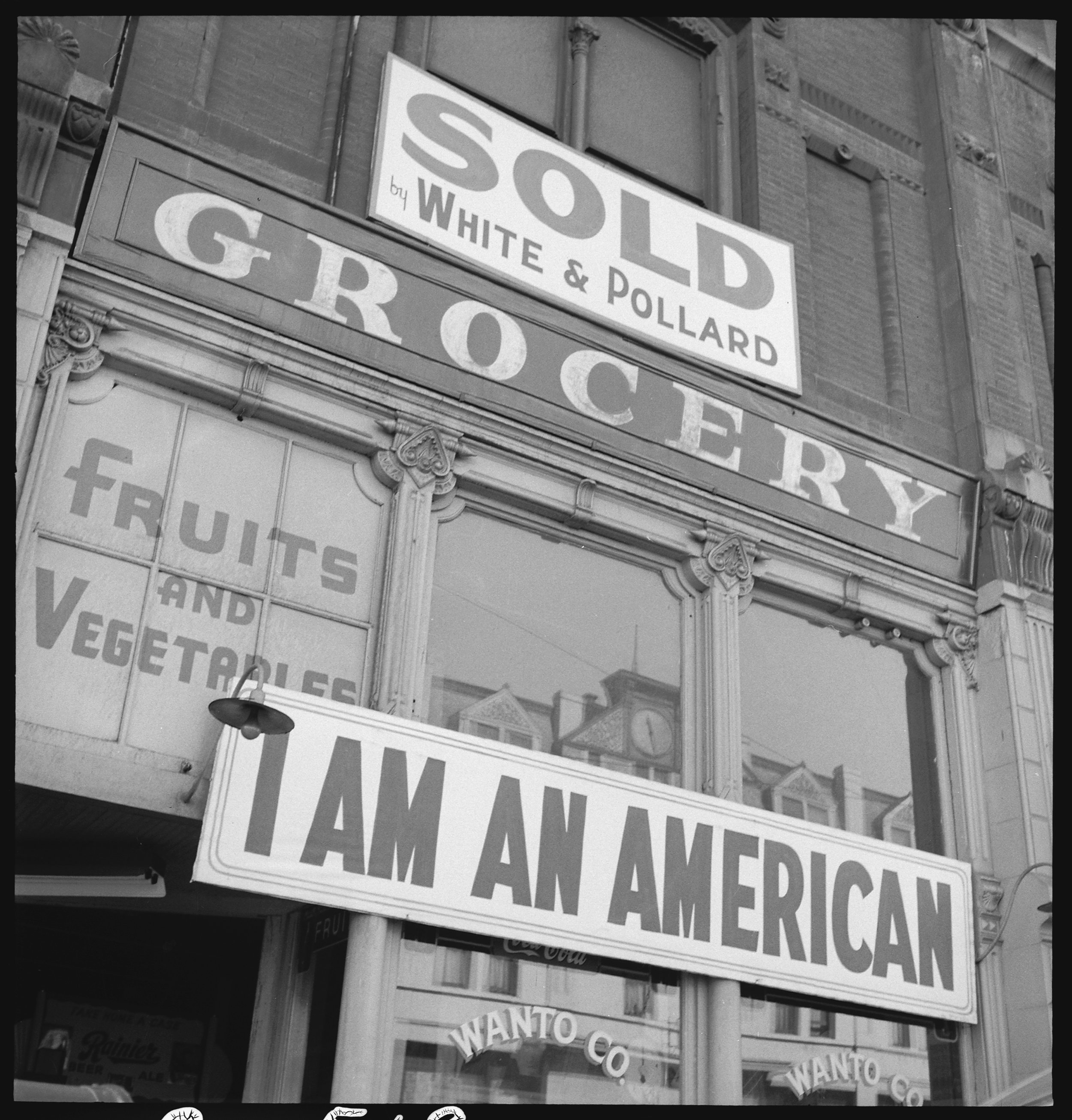

Nearly 30 years before Dr. King marched with “I AM A MAN” signs, Tatsuro Matsuda was commissioning and installing a sign that read “I AM AN AMERICAN” on his family’s storefront.

World War II came to the United States of America on Sunday morning, 7 December 1941, with a massive surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Japanese carrier attack planes and bombers, supported by fighters, numbering 353 aircraft from six aircraft carriers, attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in two waves and nearby naval and military airfields and bases. *

Dorthea Lang / Library of Congress

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, 8th December 1941, a large sign reading 'I AM AN AMERICAN', was hung on the Wanto Co grocery store (401 - 403 Eighth and Franklin Streets) in Oakland, California. The store was soon closed, as the Matsuda family, who owned it, were relocated and incarcerated under the US government's policy of internment of Japanese Americans. Tatsuro Matsuda, a University of California graduate, commissioned and installed the sign that inspired VTC Tatsuro.

Photo: Dorothea Lange / The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

The iconic photograph of this storefront was taken by Dorothea Lange, an American documentary photographer, and photojournalist best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration. Lange's photographs influenced the development of documentary photography and humanized the consequences of the Great Depression.

Lange took this photograph while working for the War Relocation Authority. The photograph soon became one of the most iconic images of Japanese Interment during WWII. *

National Archives Catalog

On February 19, 1942, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 with the intention of preventing espionage on American shores.

Military zones were created in California, Washington, and Oregon—states with a large population of Japanese Americans. Then Roosevelt’s executive order forcibly removed Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes. Executive Order 9066 affected the lives of about 120,000 people—the majority of whom were American citizens.

Canada soon followed suit, forcibly removing 21,000 of its residents of Japanese descent from its west coast. Mexico enacted its own version, and eventually, 2,264 more people of Japanese descent were forcibly removed from Peru, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina to the United States. *

Evacuation orders were posted in Japanese-American communities giving instructions on how to comply with the executive order. Many families sold their homes, their stores, and most of their assets. They could not be certain their homes and livelihoods would still be there upon their return. Because of the mad rush to sell, properties and inventories were often sold at a fraction of their true value.

Photo: Dorothea Lange / The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Until the camps were completed, many evacuees were held in temporary centers, such as stables at local racetracks. Almost two-thirds of the interns (yes, that’s what they were called) were born in the United States. It made no difference that many had never even been to Japan. Even Japanese-American veterans of World War I were forced to leave their homes.

Ten camps were finally completed in remote areas of seven western states. Housing was spartan, consisting mainly of tar paper barracks. Families dined together at communal mess halls, and children were expected to attend school. Adults had the option of working for a salary of $5 per day. The United States government hoped that the interns could make the camps self-sufficient by farming to produce food. But cultivation on arid soil was quite a challenge. *

Photo: Dorothea Lange / The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

On December 18, 1944, the government announced that all relocation centres would be closed by the end of 1945. The last of the camps, the high-security camp at Tule Lake, California, was closed in March 1946. With the end of internment, Japanese Americans began reclaiming or rebuilding their lives, and those who still had homes waiting returned to them.